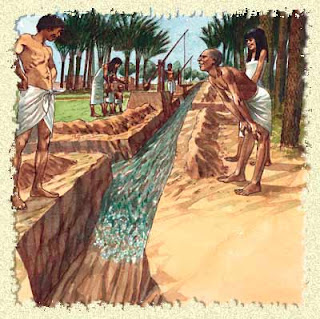

Since prehistoric times,

agriculture in Egypt depended on the waters of the River Nile and its

regular annual flood Egyptian lands, by providing water and silt. Thus,

the land was irrigated on a regular basis a year called "beds"

irrigation, which is a sharing system of agricultural land to beds by

mud barriers. The water flows into the beds through the channels. Each

channel carries the water to about eight beds, one after the other. In

this way, the land near the river banks have a greater share of water

that lands farther. Finally, the Egyptians advanced to artificial

irrigation. It aims to keep extra water left after the flood in the beds

near the banks of the river to use it to water the beds away, where

flood waters can not reach. This was accomplished by digging a series of

canals and bridges. Artificial irrigation was considered successful

cooperation required the will of the Egyptian people and government and

persistence.

Since the stabilization of the central government, Egyptians annually recorded the water level of the Nile and recorded in official records. The oldest levels record flood is the Palermo Stone from the fifth dynasty, to which 63 Nile water levels were recorded. This measure water levels continued to be used and developed until 715 AD when the Arabs built the Nilometer, or Roda measure, the name of the island, it was used. This measure was in use until the early twentieth century. Monitoring the water level of the Nile had a great effect on the estimate of taxes and the amount of land could be irrigated in the year. After each flood, the regions are responsible for channel management, while measuring the earth and the water level recording were carried out at national level.

In the Ptolemaic period, Greek temple records presented each region as an economic unit, and sent on behalf of the canal which irrigates the region, region growing, which is located on the banks of the river and is directly irrigated with its water, and land on the border of the region that could be salvaged. The irrigation system has helped to push a bed of winter crops, while the summer, the land can be cultivated mountain areas were far from the flood. Thus, when the Egyptians invented tools for raising water, such as chadouf, they managed to get two crops a year, which was considered a great advance in the field of irrigation. The chadouf was invented in the Amarna period and is a simple tool that needs two to four men to operate. The shadoof consists of a long handle weighted suspended at one end and a bucket at the other end. It can lift about 100 cubic meters (100,000 liters) in 12 hours, which is enough to irrigate a little over a third of an acre.

In the Ptolemaic era, the paddle wheel was invented to lift the water. This is a huge wheel with pots set around its circumference. The waterwheel plunges into the water then turns to lift four to six cubic meters of water. The waterwheel can lift 285 cubic meters (285,000 liters) of water in 12 hours.

Styles ancient irrigation depended strongly on the physical geography and geology of the region, and engineering skills available. Four different styles of irrigation were developed very early in the history of farming. All irrigation systems depend on water intake from natural sources and man-made canals to divert or ponds where it is applied to crops.

The Nile valley is extremely fertile and without rain. Herodotus wrote over 2000 years, "Egypt is ... the gift of the river. "Egypt depends on the Nile in a way no other nation. 97% of Egyptians live on 2.5% of its surface. The prosperity of the Nile Valley civilizations has depended throughout recorded history on the efficiency with which the central government organized the best use of river water. crops could be stored, after years of plenty, for example, and irrigation could be both constructed and maintained.

The Nile receives its water from the tropical highlands of Africa. The river receives no tributary at all for the last 1500 km of its course through the Sahara desert to the Mediterranean. In Egypt, far from its sources of water, the Nile did not flood sudden wave crests. The annual flooding begins in June as snowmelt and summer rain runoff on the river. It rises gently to its peak in late September and early October, then slowly disappears at the end of December. The Nile river is one of the most predictable in the world, and its average "flood" period of more than one hundred days, rather than being very short-lived as those of other rivers.

At first, Egyptian agriculture along the Nile was founded on the growth of winter crops, after the annual floods decreased. Egyptian Irrigation was based on several facts. There was only one water source (river) which was too powerful to control. Irrigation works had to be passive in construction, relatively high and built along the river bank so that they covered only the peak of the flood. The river valley is flat, but narrow and steep, never more than 25 km wide until it reaches the delta below Cairo. Irrigation systems could not carry water over long distances away from the river.

The ancient Egyptians built large flat-bottomed basins for crops along the banks of the river, and simple locks that diverted water in the peak of the flood. It was easy in terms of engineering, if it is not at work, arrange for proper water flow through several basins in the estate, controlled by single doors. The water was left standing in the fields of 40 to 60 days, then was evacuated crop at the right time in the growth cycle, downstream in the river. There was always plenty of water, so salt ever built in the ground and into drains and ditches was strong enough to prevent siltation. (Limon, who settled in the basins has been beneficial in two ways: it made the floors of basins uniformly flat, and he brought a lot of nutrients with floods every year.) Ditches and canals were short, and the irrigation system was very typical local.

The design of the irrigation system depended critically on knowing in advance the height of the annual flood, and the Egyptians developed a system of "nilometers" at different points along the valley. Prompt and early warning of the height of the flood as it rolled downstream from the south made a big difference to the size of the harvest. Herodotus wrote that the Egyptians "get their crops with less work than anyone in the world."

Early irrigation was rather primitive and local, and the food was not stored efficiently, so that the first civilizations were vulnerable to long-term fluctuation in the Nile floods. There was no attempt to significant water storage: since all the water from the Nile, all storage would have meant damming the river, which was well beyond the capacity of the ancient Egyptians. Therefore, their irrigation system was passive, and early Egyptian civilization depended largely on a winter crop year. After it was harvested in spring, the land lay fallow until the next flood. Only in a few places where the soil was very wet there any chance of a second crop, and, of these areas were Abydos, Memphis and Thebes, the great centers of ancient Egyptian civilization. They lay along the river upstream of the delta.

The Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom were periods of Egyptian history when a strong central government at the time of booming prosperity, followed by periods of economic stagnation and population , often accompanied by declining social, military, and artistic. It is not clear whether a strong central government has resulted in efficient irrigation and good agricultural production, or if a strong central government broke down after climate change has led to unstable agricultural production.

Comments

Post a Comment